blogpage

What the Stock Market Can Teach Us About Private Equity

Aug 14, 2025 by Richard M. Ennis

CO-AUTHORED WITH DANIEL RASMUSSEN

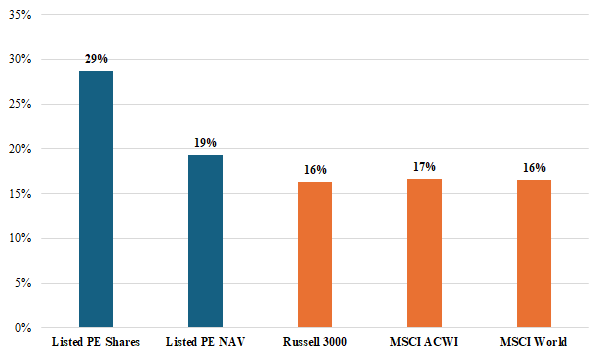

We study private equity volatility, valuation, and performance through the lens of public-market pricing of private equity interests on various European stock exchanges. We report that the volatility and stock market correlation of listed private equity (LPE) returns are greater than when determined using net asset values (NAVs). Discounts from NAV that routinely arise in the trading of LPE shares are greater and more volatile than those reported in the secondary market. LPE has underperformed the stock market in terms of risk-adjusted performance for at least the last 20 years. LPE performance has been especially weak since the Federal Reserve started raising interest rates in 2022.

Scattershot Diversification

Jul 12, 2025 by Richard M. Ennis

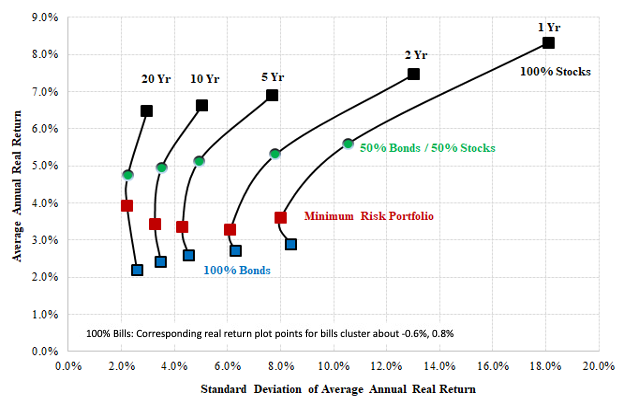

Institutional investors like active investing but not active investment risk. Sound a bit odd? In any event, in the era of alternative investing, this quirk has introduced an element of portfolio inefficiency.

Cliffwater and Ennis Don’t Agree on the Merits of Alternative Investments: Quelle Surprise!

Jun 12, 2025 by Richard M. Ennis

A leading advocate for alternative investments says they have been a boon for public pension funds. This critic of alts comes to the opposite conclusion. What do you think?

The Demise of Alternative Investments

Mar 21, 2025 by Richard M. Ennis

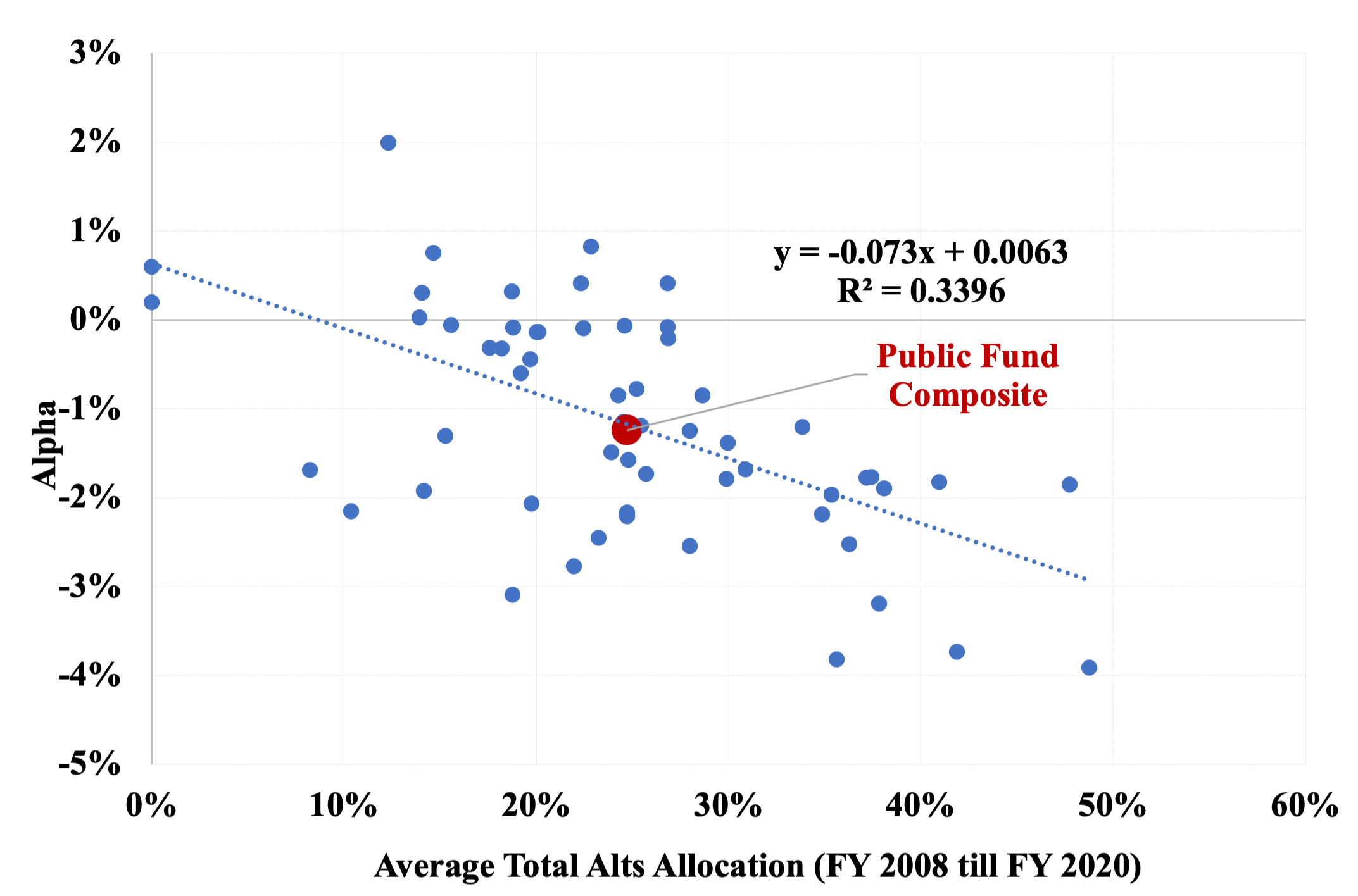

Alternative investments, or alts, cost too much to be a fixture of institutional investing. A diverse portfolio of alts costs at least 3% to 4% of asset value, annually. Institutional expense ratios are 1% to 3% of asset value, depending on the extent of their alts allocation. Alts bring extraordinary costs but ordinary returns — namely, those of the underlying equity and fixed income assets. Alts have had a significantly adverse impact on the performance of institutional investors since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 (GFC). Private market real estate and hedge funds have been standout under-performers. Agency problems and weak governance have helped sustain alts-investing. CIOs and consultant-advisors, who develop and implement investment strategy, have an incentive to favor complex investment programs. They also design the benchmarks used to evaluate performance. Compounding the incentive problem, trustees often pay bonuses based on performance relative to these benchmarks. This is an obvious governance failure. The undoing of the alts-heavy style of investing will not happen overnight. Institutional investors will gravitate to low-cost portfolios of stocks and bonds over 10 to 20 years.

The Endowment Syndrome: Why Elite Funds Are Falling Behind

Dec 06, 2024 by Richard M. Ennis

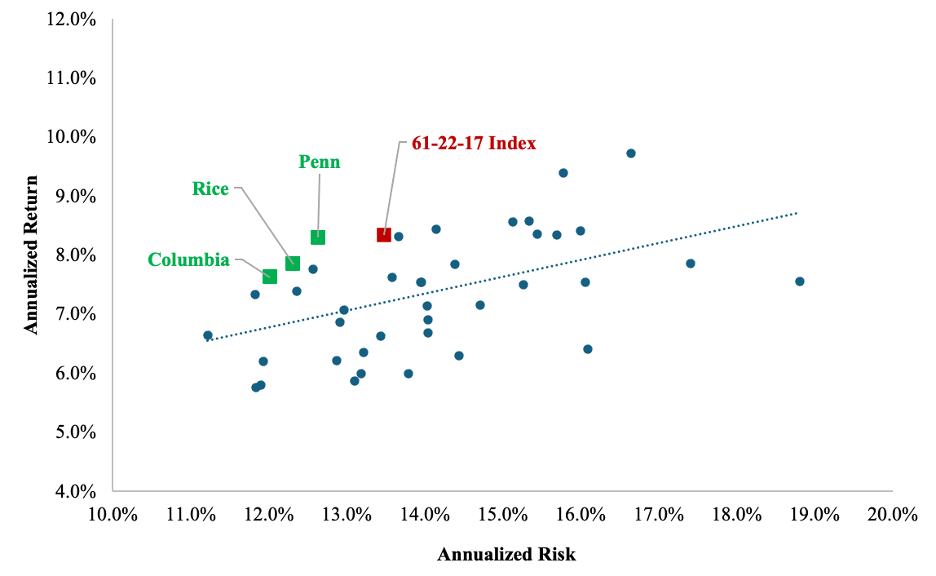

Elite endowments with heavy allocations to alternative investments are underperforming, losing ground to simple index strategies. High costs, increased competition, and outdated perceptions of superiority are taking a toll. Is it time for a reset?

Are Institutional Investors Meeting Their Goals? Spotlight on Earnings Objectives

Nov 05, 2024 by Richard M. Ennis

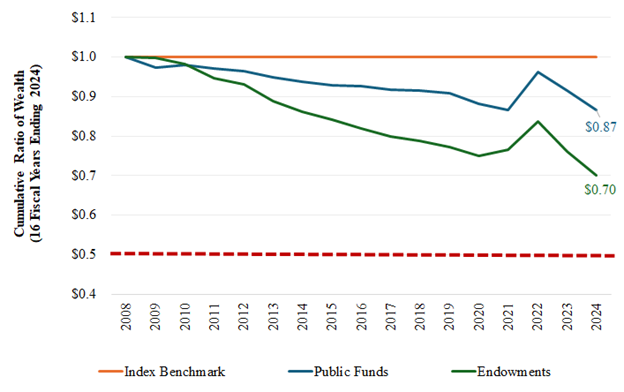

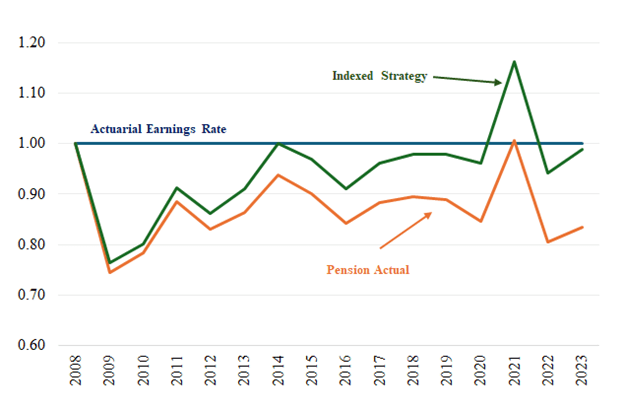

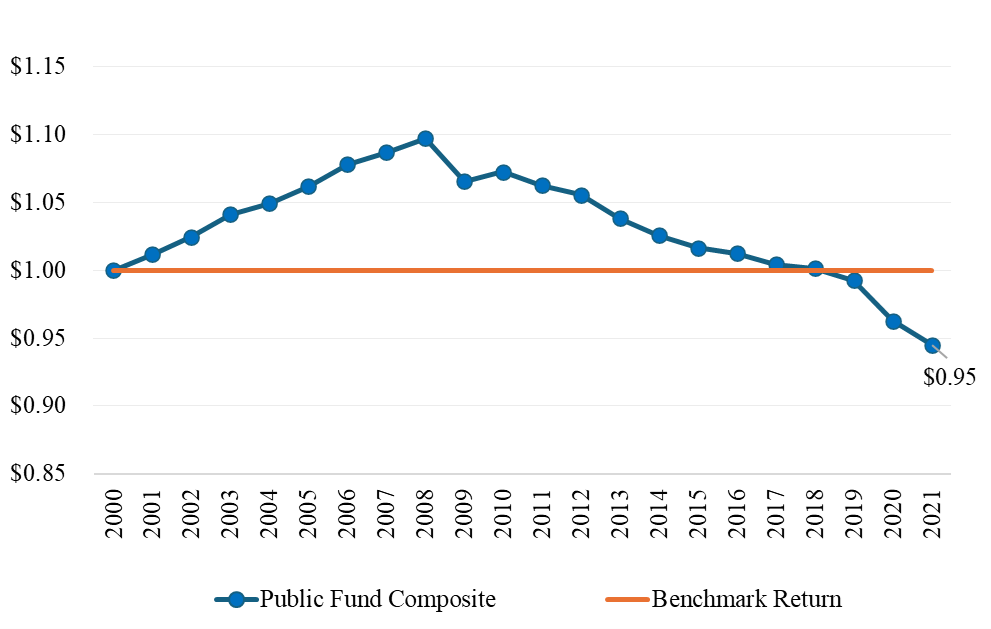

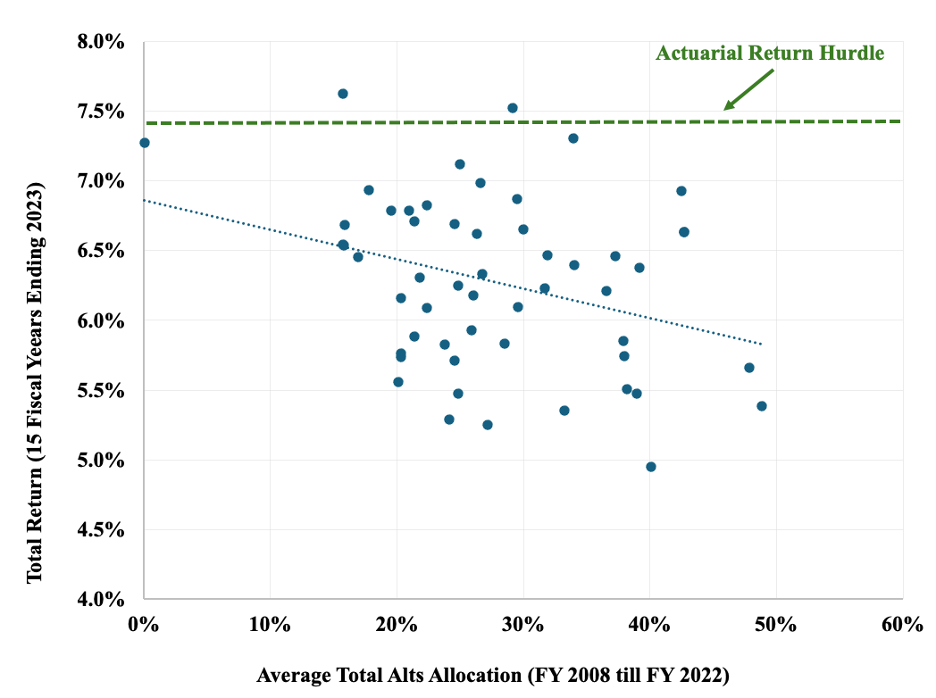

Public pension funds allocate on average 30% of their assets to expensive alternative investments and as a result have underperformed passive index benchmarks by 1.2% per year since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 (GFC). Large endowments, which allocate twice as much on average to alternatives, underperformed passive index benchmarks by 2.2% per year since the GFC. In this paper, I examine institutional investment performance from a different perspective. My focus is on whether institutions are meeting their investment goals. For public pension funds, I compare industrywide returns with the average actuarial earnings assumption prevailing since the GFC. For endowments, I compare the return earned by NACUBO’s large-fund cohort to a common goal for colleges and universities. That goal is to enjoy a typical rate of spending from the endowment, increasing over time at the rate of price inflation. In both cases, I seek to determine whether institutions have met their earnings objectives, rather than how well they have performed relative to market benchmarks.[2]

Elusive Alpha, Corrosive Cost

Aug 26, 2024 by Richard M. Ennis

The cost of institutional investing has become an impossible burden. Reduce costs. Give alpha a chance.

Hedge Funds: A Poor Choice for Most Long-Term Investors

Jun 26, 2024 by Richard M. Ennis

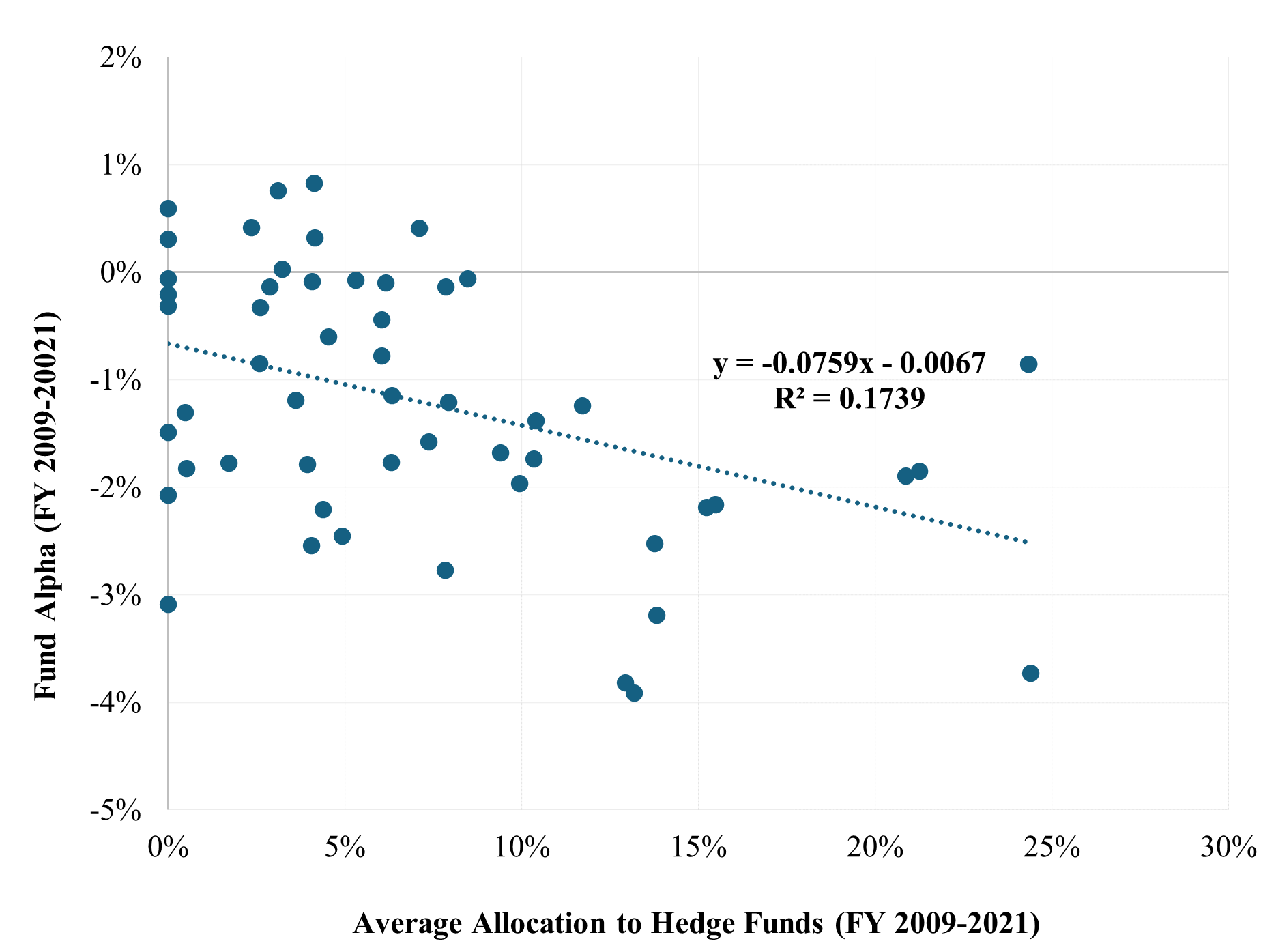

For years, hedge fund investments have reduced the alpha of most institutional investors (helped drive it negative, actually). At the same time, they deprive long-term investors of desired equity exposure. In other words, hedge funds have been alpha-negative and beta-light. For these reasons, it is difficult to see a strategic benefit to having a diversified hedge fund allocation in the mix for most endowment and pension funds. If, however, an institution has access to a few truly exceptional hedge funds and can resist the temptation to diversify hedge fund exposure excessively, a small allocation may be warranted.

The Long-Run Performance of Public Pension Funds in the US

May 30, 2024 by Richard M. Ennis

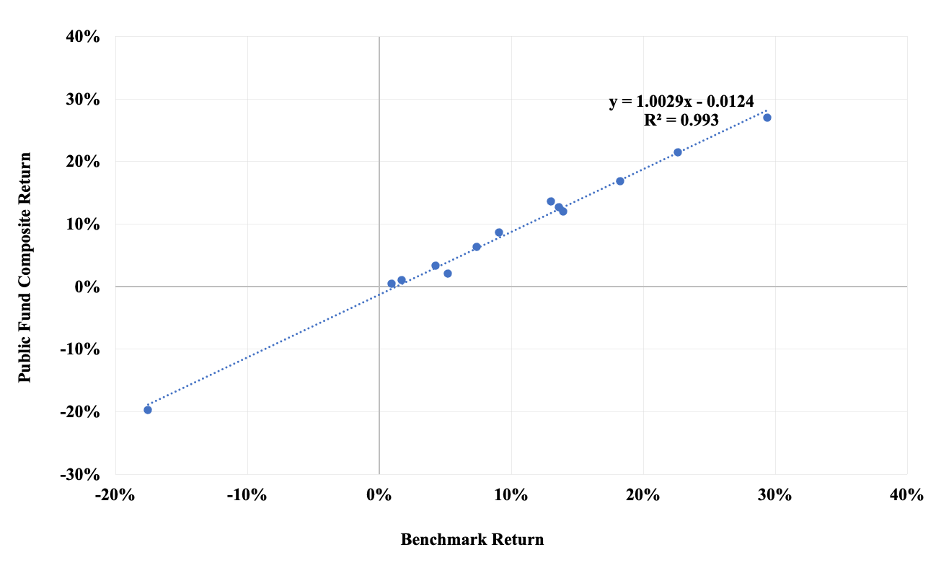

Public pension funds in the US performed well prior to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, and their alternative investments contributed to the success. Then they experienced an abrupt, sustained reversal of fortune. Alternative investments again were key. Overall, public pension funds underperformed market index benchmarks by a cumulative (unannualized) five percentage points between 2001 and 2021. Might we expect another reversal, with public funds staging a comeback?

How Hidden Costs Undermine Public Pensions in the US

May 02, 2024 by Richard M. Ennis

Public pension plans in the US incur exorbitant asset management costs. Most spend a lot and get nothing for it. High cost has hindered efforts to realize their actuarial return requirement. It has resulted in poor performance pretty much across the board. And yet, very few plans provide a full accounting of the costs they incur. Some still fail to net all their investment expenses from the returns they report. High cost is the Achilles heel of the public pension system in the US. It’s time to bring costs down, way down.

Unexceptional Endowment Performance

Apr 07, 2024 by Richard M. Ennis

Conventional wisdom has it that the investment offices of leading universities are exceptional in the realm of institutional investing. Siegel (2021), for example, provides a fulsome account of what he sees as their competitive advantages. He concludes, “Endowment funds have...structural advantages...that should allow them to earn above-market risk-adjusted returns in the long run.” Hmm. Is endowment exceptionalism real? Is it myth? A little of both?

Second-Guessing CalSTRS on Investment Strategy: A Case Study

Mar 30, 2024 by Richard M. Ennis

“CalSTRS to Weigh New Opportunistic Sleeve,

Eliminates 55% Limit on Private Assets”

So goes the headline of a recent article in Pensions & Investments, the industry newspaper for institutional investors. The article describes a proposed new allocation of up to 5% of fund assets. P&I reports, “The new portfolio would give CalSTRS flexibility ‘to identify, research and incubate new and compelling strategies’ that may fall beyond existing asset classes because of their structure, their benchmark or their thematic focus.”

California State Teachers Retirement System (CalSTRS), with $319 billion in assets at June 30 of 2023, has long been an investor in alternative asset types. Its allocation to alternatives rose from about 10% of assets in 2001 to about 44% in 2023. The recent alts figure compares to an average of 34% for large public pension funds in the US. Upon reading the P&I article, I decided to explore the merit of CalSTRS’s proposed strategic shift, which is likely to place even greater emphasis on controversial alternative asset types.&a

Hogwarts Finance

Oct 26, 2023 by Richard M. Ennis

CIOs and consultant-advisors oversee about $10 trillion of institutional assets in the US. They have underperformed passive management by one to two percentage points a year since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 (GFC). They rely heavily on expensive alternative investments; and the more they have in alternatives, the worse they do. Large institutions use scores of managers, making them high-cost closet indexers. Inefficiency abounds.

What is lacking in institutional fund management today? Intellectual rigor, for one thing. The professionals are ignoring their canon. Lawyers coming before the bar are expected to know the law. Physicians, conspicuously, in my experience, attempt to adhere to the best medical science. Engineers do not improvise when designing bridges. But the people managing institutional assets behave not like they attended the Booth, Säid or Wharton schools to study finance but Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.

Endowments in the Casino: Even the Whales Lose at the Alts Table

Sep 21, 2023 by Richard M. Ennis

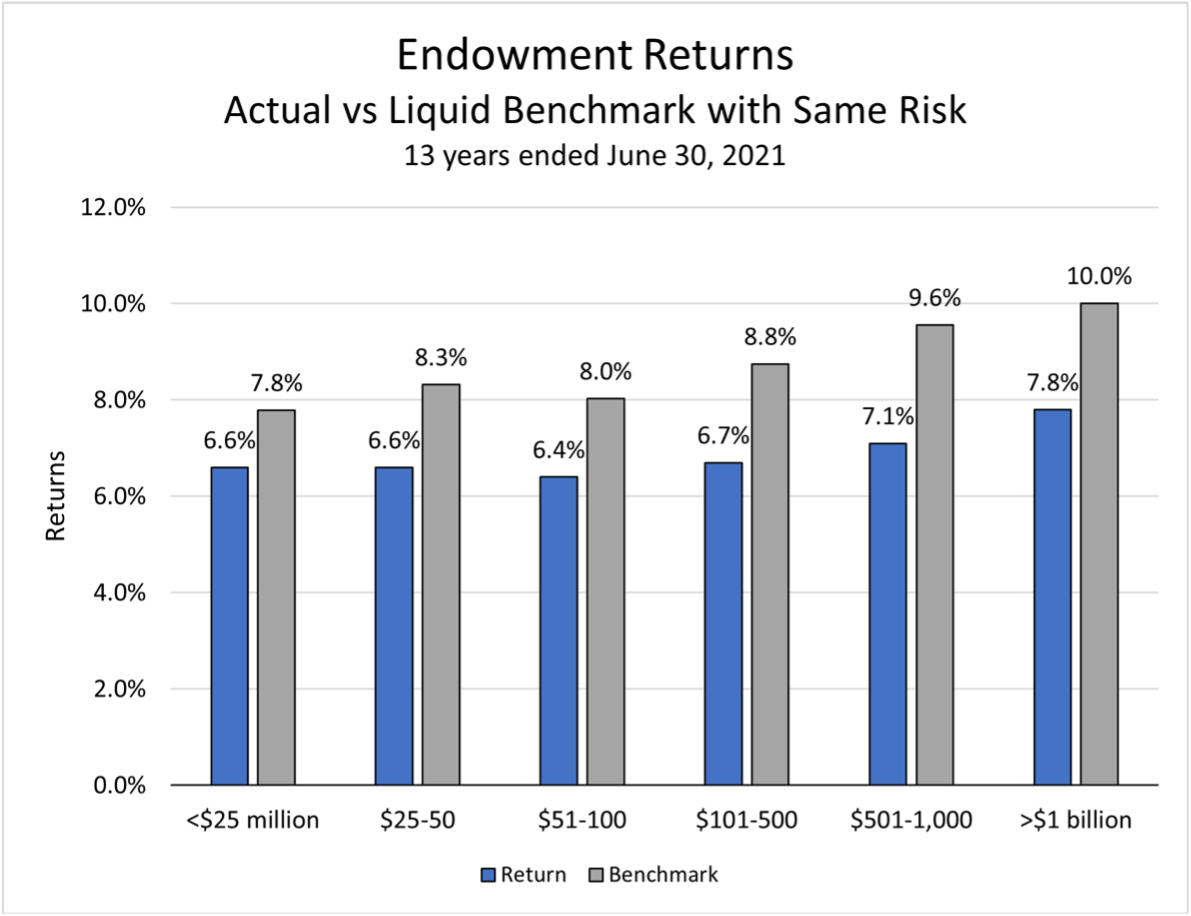

The alternative investments of college and university endowments have detracted from the schools’ performance across the board since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Large endowments—ones with greater than $1 billion in assets—appear to have handled their alternative investing better than the smaller ones. But whatever skill the big ones might bring to bear has not been enough to make them winners with these controversial investments.

Have Alternative Investments Helped or Hurt?

Aug 03, 2023 by Richard M. Ennis

Despite all the attention paid to alternative investments in recent years, there has been little study of their impact on the performance of institutional investment portfolios, e.g., those of pension plans and endowed institutions. This paper attempts to help fill the void. It shows that, since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, US public-sector pension funds realized a negative alpha of approximately 1.2% per year, virtually all of which is associated with their exposure to alternative investments. While exposure to private equity neither helped nor hurt, both real estate and hedge fund exposures detracted significantly from performance. Institutional investors should consider whether continuing to invest in alternatives warrants the time, expense and reduced liquidity associated with them.

Excellence Gone Missing

May 12, 2023 by Richard M. Ennis

Managers of institutional portfolios have long been seen as among the elite in the investment field. They typically possess advanced degrees and/or other professional credentials. They are fiduciaries for the largest and most complex investment portfolios on the planet. Many are paid fabulously. In terms of the collective merit of their work, however, I see room for improvement. Indeed, I question the excellence of much of institutional investing as it is practiced today.

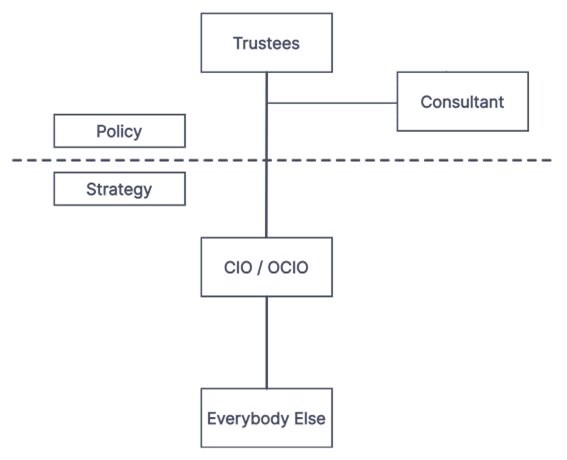

Disentangling Investment Policy and Investment Strategy for Better Governance

Jan 03, 2023 by Richard M. Ennis

Institutional investors have failed to apprehend the difference between investment policy and investment strategy. Most trustees, CIOs and consultants don’t appear to know where one leaves off and the other begins. Trustees should concern themselves with institutional investment policy, the principal focus of which is controlling risk and ensuring liquidity. In practice, however, trustees have allowed their deliberations to encompass elements of active investment strategy. Consequently, performance accountability has become clouded. This paper discusses how trustees can fix the problem.

An Open Letter to Investment Consultants

Dec 27, 2022 by Richard M. Ennis

Institutional investors’ performance has been lackluster at best. Most use one or more investment consultants. I believe consultants can do a better job of helping their clients achieve satisfactory results. Here are some recommendations for doing so.

Lies, Damn Lies and Benchmarks: An Injunction for Trustees

Oct 19, 2022 by Richard M. Ennis

Most institutional investors, such as public pension funds and endowments, report their performance using biased benchmarks. The benchmarks are biased downwardly, meaning their returns tend to be less than a fair return for the market exposures and risk exhibited by the institutions’ portfolios. Significant samples of both fund types exhibit benchmark bias in the range of 1.4 to 1.7 percentage points per year. This bias enables a sizable majority of both types of funds to report outperforming their chosen benchmarks when, in fact, most underperform an appropriate passive-management benchmark by a wide margin. Benchmark bias masks serious agency problems in the management of institutional funds. For example, fund staff and consultants have strong incentives to justify complex, costly, multi-asset-class portfolios, for which they themselves are the benchmarkers. Trustees may feel they have no choice but to accept the benchmarking and reporting by staff and consultants, but this only perpetuates the problem. At the very least, investment trustees should step up and take control of benchmarking and performance reporting. For they are the ones charged with watching the watchmen.

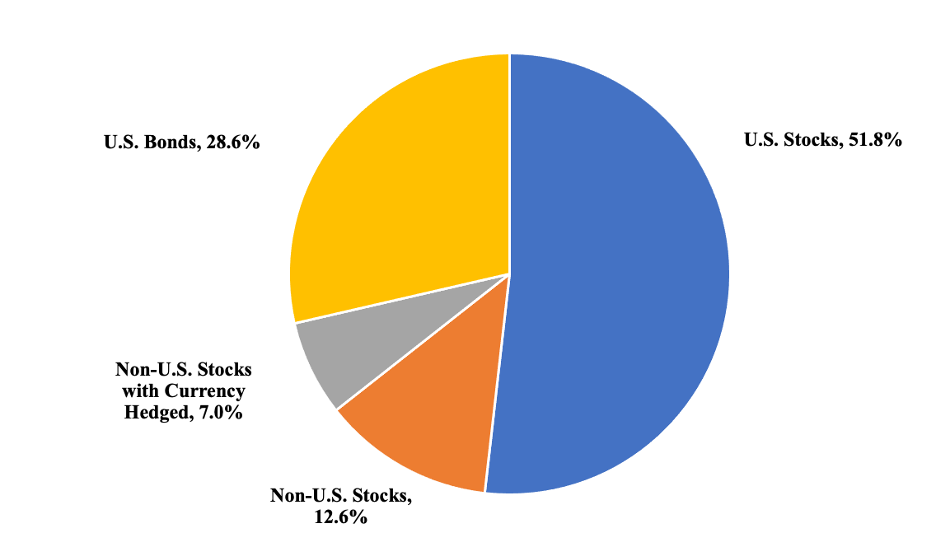

A Universal Investment Portfolio for Public Pension Funds: Making the Most of Our Herding Ways

Jun 16, 2022 by Richard M. Ennis

Herding is human nature. There is ample evidence of it in the management of public pension funds in the United States. Their effective equity exposures cluster about an average of approximately 70%. Extreme diversification is universal. These two aspects of herd behavior have proven benign. Where herding has had a detrimental effect is the funds pouring more than a trillion dollars into alternative investments after alts ceased adding value to institutional portfolios more than 10 years ago. One might say two out of three ain’t bad. And yet, the heavy use of active management, and alts, in particular, has cost the funds dearly. Public fund managers need to understand that their strength is not active money management. Rather, it is their potential to become the lowest-cost producers of investment returns on the planet. This article argues in favor of a one-size-fits-all approach to managing public pension investments—namely, embracing a Universal Investment Portfolio.