Disentangling Investment Policy and Investment Strategy for Better Governance

Large endowments and public pension funds use an average of more than 100 managers and generate returns that are nearly fully explained statistically by market indexes. Yet, owing to inefficient diversification, they typically underperform by the full margin of their very substantial costs. I estimate that since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, public pension funds have underperformed passive management by 1.2% per year; for large endowments, the figure is at least 2.2%.[1] Many institutions mistook alternative investments for asset classes in their own right (i.e., as providing an enduring diversification benefit) and invested in them in wholesale fashion. But most alternatives proved to be merely expensive active investment strategies, with merits as short-lived as those of other active strategies and which respond to the same systematic return drivers as stocks and bonds.[2] Making matters worse, there has been an unfortunate trend among institutional funds to contrive benchmarks with returns that are biased significantly downwardly.[3] These are commonly referred to as strategic (or custom) benchmarks. As a result, most funds give the impression that they are performing competitively compared with passive management when in fact they are not.

I have been pondering these problems and their genesis. We can probably blame them on a combination of things: failure to appreciate the competitiveness and degree of integration of markets, private as well as public; ambition; overconfidence; infatuation with alternative investments past their time and beyond their merit; groupthink; excessive investment expense; and governance lapses. Here I speak to a particular governance issue that, to my knowledge, has gone unaddressed in our literature and been largely ignored in practice. Namely, institutional trustees allowed themselves to conflate investment policy and investment strategy. What is the difference between the two and why does it matter?

POLICY VS. STRATEGY

Investment policy is the domain of trustees. It is principally the expression of the institution’s risk tolerance and liquidity requirements. It describes what an investment manager needs to know about its client before embarking on portfolio management. Investment strategy is the domain of investment professionals attempting to add value through various forms of active management. The two should not overlap.

Investment Policy

The distinction I draw between policy and strategy rests on the premise that the great majority of institutional investment trustees are part-time, unpaid laypersons with respect to investing. In other words, they are not investment experts. Trustees are responsible for establishing institutional investment policy based on their understanding of the circumstances of the institution they serve. The starting point is establishing whether the investment task is liability matching or asset allocation (efficient portfolio construction). They need to gauge risk tolerance, i.e., the sensitivity of the portfolio’s principal stakeholder(s) to fluctuations in surplus value (for liability matchers) or asset value (for asset allocators). For the purpose of liquidity planning, the trustees should have before them estimates of the timing and amount of future distributions from the portfolio as well as projected cash inflows. Although the work of the trustees is primarily inward-looking and interpretative, it can encompass aspects of investment management where there exists widely accepted theory and substantial empirical evidence. In this regard,

- It is customary and appropriate for trustees to emphasize equity investing (commensurate with risk tolerance) in the investment policy statement (IPS). Research emanating from the University of Chicago in the 1960s (and updated regularly) shows that the return of US common stocks has greatly exceeded that of bonds over the long run.[4]

- Perhaps the most fundamental tenet of prudent investment is that it pays to diversify.[5] No special investment expertise is required to appreciate the wisdom of this. Tempering equity risk with bonds is a tried and true form of diversification. The correlation coefficient of US stocks and government bonds has averaged 0.01 over the long run.[6]

- Trustees may choose to limit the use of active management. There is solid theory and considerable evidence of the type laypersons can grasp that active management typically doesn’t pay. In the latter regard, many trustees will have read Burton Malkiel’s A Random Walk Down Wall Street, which has been in print for more than 50 years, or Charles Ellis’s Winning the Loser’s Game, both of which lay out in plain English the challenge of beating the market.[7] And now, with more than half of mutual fund dollars being indexed, it is evident that even a great swath of individual investors has made the investment policy choice to invest passively.[8]

These matters are within the ken of the reasonably well informed trustee. Work in the policy realm is foundational and vitally important. It warrants a serious effort on the part of trustees. As part-time laypersons, trustees need expert help in dealing with these issues. (More on this later.) Ultimately, trustees must distill the results of their work in an IPS to guide investment experts in managing the portfolio. What are the limits of policy? It ends where subjective, expert asset selection takes up. This is the realm of strategy, to be undertaken by a chief investment officer (CIO) or outsourced CIO (OCIO) on behalf of the trustees.

Strategy

Investment strategy is the domain of a CIO or an OCIO — an accomplished and adequately resourced investment expert, in other words. Strategy, conducted within trustees’ risk-and-liquidity policy framework, involves the following:

- Determining the allocation of assets between active and passive investments, in conformance with any limit expressed in the IPS.

- Whether to make active investment decisions in-house or to delegate them to specialized managers.

- Selecting active strategies and managers, including whether to invest in alternative asset types.

- Allocating assets among managers and strategies.

- Selecting individual assets

It is critical that all parties to the investment management task understand the division of labor described here and that a delegation has occurred. In 1977, before alternative investing began to flourish, Doug Love contributed a one-page essay to Financial Analysts Journal that describes these matters eloquently.[9] Titled “Investment Policy vs. Investment Strategy,” Love’s essay draws the critical distinction between the two. The essay is so fine and so brief I chose to condense it a bit, taking minor liberties in the interest of flow, rather than attempting to paraphrase or explain it.

Investment strategy presumes that markets are not efficient and concentrates on which risks to take and when in exploiting perceived inefficiencies. A strategy has value for as long as it takes for it to be employed by others. An investment policy, on the other hand, is a decision with an indefinite (though not infinite) time horizon, taken with regard to the ability to assume investment risk. The investment policy task is to determine how much risk to take as a matter of principle, independent of current outlook.

The client is obliged to make a policy decision, whether he is using “passive” money managers emphasizing returns to holding assets, or “active” money managers emphasizing returns to trading assets. When the client’s analysis of policy is based on a specific outlook, however, things begin to go awry. They go awry because, if the analysis includes an outlook, the resulting policy is in fact a strategy and will soon be irrelevant.

The existence of a professional money management industry presupposes a division of labor between savers and investors. It is the responsibility of savers, particularly individuals charged with savings and investment programs, to set policy. It is the responsibility of professional investors to identify potentially profitable strategies. Without a clear distinction between investment policy and investment strategy, however, it is not possible to effect a meaningful division of labor between professional investors and their clients [emphasis added]. Confusing the roles of those responsible for policy and those responsible for strategy results in a serious problem, because the accountability of the latter’s performance is muddied.

Love’s “division of labor” is an elegant construct that makes clear a delegation is taking place. The client (often a fiduciary or fiduciaries serving absent stakeholders) is responsible for establishing the basic risk parameters of the undertaking. The investment manager is charged with performing skillfully within those parameters. Implicit in the delegation is the responsibility of the client to hold the investment manager accountable for results. This is not an adversarial situation. Nor is it a collaborative effort. Rather, it is simply that the client must remain objective in monitoring and evaluating the manager’s work. If the client begins to embrace strategy, it will find itself on the slippery slope to muddied accountability that Love described.

CONFUSING POLICY AND STRATEGY

Failure on the part of clients to maintain the division of labor Love described more than 40 years ago is precisely what happened in the field of institutional investing. Nowadays, investment staffs and consultants have entered the picture along with investment managers, but Love’s sense of things remains unchanged. Here is how things have unfolded:

- Most institutional trustees have failed to apprehend the crucial difference between policy and strategy. Some choose to participate in technical asset allocation studies along with staff and consultants. They allow themselves to become involved in the approval of outlook-dependent strategies, such as private market investments, hedge funds and other active strategies. They have failed to remain sufficiently objective and, in many cases, sufficiently removed from the investing itself. Indeed, in many cases, trustees favor a collaborative approach with staff, consultants and/or investment managers over dispassionately monitoring a delegated function. They allowed their investment staffs/consultants/OCIOs to water down benchmarks. (See note 3.) Consequently, too many trustees are unaware of the true performance of their funds. Others, aware of a performance problem, are at a loss to know what to do about it. Absent a clear division of labor and rigorous monitoring of the delegated function, trustees are destined to be adrift.

- The investment consultant, the independent advisor to trustees that came into its own in the 1980s, failed to advocate firmly for the division of labor, allowing strategy to become conflated with policy. Consultants found themselves working closely with institutional investment staffs as well as trustees: some lost sight of who brung them to the dance. They allowed the definition of an asset class to become fuzzy, with the embrace of active strategies creeping into the client’s IPS. As things eventuated, consultants contributed to the trend of replacing passively investable benchmarks, i.e., simple combinations of broad market indexes, with downwardly biased “strategic” ones.[10]

- Investment managers encouraged clients to take an active interest in their work. They sought clients’ approval of investment guidelines and regularly discussed strategy with clients. Some sponsored “educational” sessions with clients outside of official meetings (casting the manager in the role of host and the client as guest.) Not infrequently, managers would discuss individual holdings with clients in the course of portfolio reviews (a sharing of war stories). This gradual process of engagement and familiarization resulted in some clients developing, unwittingly perhaps, an embrace of strategy or affinity for the manager. Clearly, it is in the interest of the investment manager to have the client embrace its strategies. To the extent that occurred, it eroded the division of labor and co-opted trustees.

- The handling of alternative investing was, in my opinion, also a contributing factor to the governance lapse described here. Alternative investments are active investment strategies. Alternative asset managers (seeking a share of the pie) and consultants (seeking to be seen as adding value), however, presented them as constituting “asset classes” with reliable and enduring diversification properties like that of stocks with bonds.[11] Thus, to many trustees, including alternative investments in the portfolio was viewed as a sound diversification move and seemed to jibe with the concept of setting policy and warranting a place in the IPS. In this way, clients wound up with a degree of ownership of allocations to pseudo-asset classes such as private equity, real estate and hedge funds, which, as I have said, are active strategies whose returns vibrate systematically with those of stocks and bonds. Clients developed fixed allocations to various categories of alternatives and began to invest widely in them in the (misguided) spirit of diversification. According to a 2020 Brief by The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, large public pension funds had an average of 182 investment managers and 144 of them were for alternative investments. Thus, in my judgment, an important source of the funds’ inefficient diversification results from their wholesale approach to investing in pricey alternative investments; and most of this activity was approved by trustees.

More than four decades after Love published his essay, we observe institutional investors using more than 100 managers and underperforming by the full margin of their now-very-substantial costs. Nowadays, strategy is near impossible to distinguish from policy. What can be done to fix the problem and, hopefully, make institutional investing more efficient?

DISENTANGLING POLICY AND STRATEGY

Ultimately, this paper is about the optimal organization of the institutional investment process, including clarifying the roles and responsibilities of key participants, to maximize the effectiveness of institutional investing.

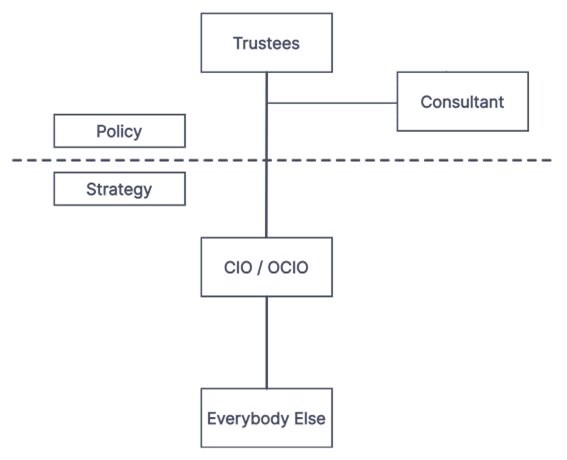

Organization

As things have eventuated, a new delineation of the roles of trustees and service providers is warranted. Large funds would continue to have a full-time CIO and staff. The trustees of those funds should delegate full discretion exclusively to the CIO. Smaller funds should engage an outsourced CIO (OCIO), to whom the same full discretion would be delegated. I do not believe any funds should operate with the traditional trustee-consultant model, in which the consultant advises trustees in connection with strategic decisions (as well as policy) and performs performance evaluation. Under this arrangement, the consultant faces insurmountable conflicts.

The Role of the (Truly) Independent Consultant

What is the role of the independent consultant in a world with a clear delineation between policy and strategy and fully delegated strategic decision-making? I see these functions:

- The consultant, which reports to and works exclusively for the trustees, would be the institution’s principal resource for investment policy analysis. It would help trustees establish investment purpose, be it liability matching or conventional efficient asset allocation. It can help trustees assess their tolerance for risk and assess the potential efficacy of active investing relative to passive management. In short, the consultant would be responsible for helping trustees engineer the portfolio in advance of asset management. The consultant would then draft the IPS. This is profoundly important work.

- It can help trustees understand the division of labor, how to bring it about, and how to preserve it over time.

- The consultant can help funds without a CIO to select an OCIO.

- It can help identify an appropriate passively investable benchmark and in ongoing performance monitoring. It can monitor investment operations and report to trustees re compliance of investment activities with the IPS.

- The consultant can educate trustees in the financial economics of institutional investing, i.e., the theory and evidence accumulated over decades that has a bearing on trustees’ work. (Currently, trustees don’t get a lot of this inasmuch as those that serve the trustees are primarily engaged in attempting to triumph over theory and evidence.)

The consultant would thus have no role in the development or implementation of strategy, and it would operate independently of the investment staff or OCIO.[12] It would bring substantial resources to bear in its work. I believe that all trustee groups, regardless of asset size or the sophistication of their investment staff or OCIO, should use an independent consultant in this manner. It is essential in bringing about and preserving the division of labor and keeping trustees on a firm footing. Exhibit 1 illustrates sound functional organization for institutional investors.

Exhibit 1

Proper Organization for Institutional Investing

Bringing About the Division of Labor

The trustees should make an assessment of their process to determine where it might overlap with the play of strategy in asset management. They should let professionals establish strategic asset allocation, make the decision to invest in alternatives, and handle all aspects of manager selection and retention. Trustees can decline to discuss strategy in depth to lessen the likelihood of their developing an attachment to any. There is no good reason for trustees to approve investment guidelines: What sense does it make for the layperson to provide the expert with highly particular guidance? Trustees need never meet with individual managers engaged by the CIO or OCIO. Nor do they need to engage in discussion of investment operations apart from ensuring that they conform with the IPS. (The consultant can help here.) Trustees can decline to receive frequent and/or detailed performance reports. They might even find meeting less frequently (some investment committees meet monthly) more appropriate once they have a clear understanding of their task and the division of labor that is to take place.

Ongoing Trustee Oversight

So, having prepared an IPS and delegated investment management to a CIO or OCIO, what do trustees do? They monitor performance of the total fund relative to a simple passive benchmark, one that is under their control and which only changes when the trustees believe a fundamental change of institutional circumstance warrants a revision of investment policy — no benchmark tweaking to reflect shifting investment strategy or the trustees’ emotional state during turbulent markets! They receive reports from the CIO or OCIO and the consultant, respectively, regarding their work. They discuss these reports in periodic meetings with staff (or OCIO) and consultants. They form opinions about the effectiveness of investment management and their confidence in the CIO or OCIO. They may modify a restriction on active management that may exist in the IPS, based on their monitoring and evolving confidence in the principal investment manager. They may pay a bonus for excellent results or express disappointment when results disappoint. They may replace the CIO or OCIO if they lose confidence in them.[13] This is what trustees ought to be doing in investment oversight, leaving all the inside baseball to the professionals in their respective areas of expertise.

DISCUSSION

There is much not to like about this proposal.

The status quo for most CIOs and OCIOs is probably a good deal more congenial than what I propose. Their tenure would likely be less certain with evaluations of their performance being made by truly disinterested parties. For sure, many CIOs would be uncomfortable with loss of influence (or outright control) over benchmarking and performance reporting. But the practice of investment staff members receiving bonuses for outperforming a benchmark they have had a hand in creating must come to an end. So must the use of biased benchmarks. Without these changes, there is no hope for institutional investing.

Like moths drawn to a flame, consultants have long been eager to have a hand in strategy. Many among them now quietly acknowledge the conflicts of interest they face, realizing that they have been co-opted professionally by a combination of forces: (a) clients’ unceasing eagerness to beat the market and (b) the awesome power of the investment management industry in selling its services. Some consultants would welcome the professional freedom to advise trustees exclusively, sans a business interest in whether or not strategy adds value. This is very substantial, meaningful professional work for consultants. They simply need to have trustees welcome them in the role as trustees did in the early days of consulting.

Many trustees will be apprehensive about adopting the model I propose. Some would miss being part of the scrum with investment staff, consultants and managers at quarterly meetings, which they find stimulating and possibly more interesting than their day jobs. But trustee entertainment is not a goal of sound governance. Others would prefer a collaborative environment to a more formal one that entails hard-nosed supervision. These cordial folks will just have to toughen up a bit and accept their responsibility. And some may fall prey to the Dunning-Kruger effect,[14] failing to realize they are out of their depth in attempting to participate in strategic decision-making for a complex, multi-billion-dollar fund. But trustees have an obligation to stakeholders to make a frank assessment of their role and performance in investment oversight. They must continually strive to educate themselves and be prepared to move beyond their comfort zone. Far too much is at stake for them to do otherwise. And only the trustees are in a position to fix things.

This proposal has two essential elements. One is extricating trustees from the realm of strategy. The other is removing benchmarking and performance measurement from the influence of the CIO or OCIO and placing it in the hands of a disinterested third party. The proposal is not a panacea for overcoming the performance problems of institutional funds. Adopting its essential elements, however, is an important step in the right direction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful for the contributions of Anonymous, Matthew Arnold, John Bass, Barclay Douglas, Anders Ekholm, Charles Ellis, Don Ezra, Rudy Fichtenbaum, Barry Gillman, Roger Ibbotson, Antti Ilmanen, Jeffrey McCurdy, Paul O’Brien, Christopher Philips, Trym Riksen, Brian Schroeder, Michael Sebastian, William Sharpe and Trey Shipp.

REFERENCES

Duignan, B. 2022. "Dunning-Kruger Effect." Encyclopedia Britannica, August 18. https://www.britannica.com/science/Dunning-Kruger-effect.

Ellis, C.D. 2021. Winning the Loser's Game: Timeless Strategies for Successful Investing, Eighth Edition. McGraw Hill.

Ennis, R.M. 2020. “Institutional Investment Strategy and Manager Choice: A Critique.” Journal of Portfolio Management (Fund Manager Selection Issue): 104-117.

——. 2022a. “Cutting through the Fog of Asset Class Labels.” The Journal of Investing, 31 (2) 6-10.

——. 2022b. “Are Endowment Managers Better than the Rest?” The Journal of Investing, 31 (6).

——. 2022c. “The Modern Endowment Story: A Ubiquitous Equity Factor.” Journal of Portfolio Management, November.

——. 2023. “Lies, Damn Lies and Benchmarks: An Injunction for Trustees.” The Journal of Investing, forthcoming. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4253186.

Huang, D. 2022. “Passive Investing, Mutual Fund Skill, and Market Efficiency.” Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4190266 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4190266.

Ibbotson, R.G. and J.P. Harrington. 2021. Stocks, Bonds, Bills and Inflation. CFA Institute.

Love, D.A. 1977. “Investment Policy vs. Investment Strategy.” Financial Analysts Journal, March-April, p. 22.

Malkiel, B.G. 2019. A Random Walk Down Wall Street: The Time-Tested Strategy for Successful Investing. W. W. Norton & Co.

[1] See Ennis (2022b)

[2] See Ennis (2020).

[3] Forty-two of 46 large US public pension and endowment funds I examined used benchmarks with 10-year returns that were less than those of fund-specific, passively investable benchmarks that I created for them using returns-based style analysis. The average benchmark bias of the pension funds was 1.7% per year. Endowments averaged benchmark bias of 1.4% per year. See Ennis (2023).

[4] See Fisher and Lorie (1964), Ibbotson and Sinquefield (1976) and Ibbotson and Harrington (2021).

[5] See Fisher and Lorie (1970).

[6] See Ibbotson and Harrington (2021).

[7] See Ellis (2021) and Malkiel (2010).

[8] See Huang (2022).

[9] See Love (1977).

[10] Again, see Ennis (2020, 2023).

[11] Stocks and bonds, in combination, are the quintessential diversifiers. As previously noted, the correlation coefficient of large cap US stocks and US Government bonds averaged 0.01 between 1926 and 2020. See Ibbotson and Harrington (2021). Real estate, venture capital, private equity and hedge funds, on the other hand, have positive correlation coefficients with stocks in the range of 0.5 to 0.9, despite their typically smoothed returns. See Ennis (2022c).

[12] The CIO might engage one or more consultants to assist in portfolio construction and/or manager research. Such consultants would be other than the one that serves trustees in the areas of investment policy and performance measurement.

[13] The arrangement I propose is likely to bring into relief the question of CIO retention, always a touchy subject. One “benefit” of shortcomings in performance evaluation that I have touched on here (and discussed in depth elsewhere) is that trustees are currently not often confronted with performance reports that raise serious questions about CIO retention. In contrasting governance spheres, we are much more likely to read of the sacking of, say, the Disney CEO than we are of the CIO of an Ivy League school or a 50-billion-dollar public pension fund.

[14] “The Dunning-Kruger effect, in psychology, [is] a cognitive bias whereby people with limited knowledge or competence in a given intellectual or social domain greatly overestimate their own knowledge or competence in that domain relative to objective criteria or to the performance of their peers or of people in general.” See Duignan (2022).